Our Shared Symbology of Dread

How Carrie Bradshaw helped me connect with my ancestors, process my emoji trauma, and come to accept things as they are

Recently, I found myself watching episode two of the latest season of HBO’s And Just Like That…, titled, fittingly, ‘The Rat Race.’

Now, I feel the need to be transparent from the start here. I acknowledge the choice phrasing of I found myself watching implies a certain passivity or lack of agency on my part. It might suggest, perhaps, a sense of coma or fugue state emergence. That maybe I blacked out. Disassociated and came to, resuming consciousness only to find Miranda gushing about Bi Bingo, the bi-sexual dating show she learns to hate watch in the episode.

While the word choice is very deliberate, I must admit it is something of a half-truth by design; albeit a fitting one. Because I made the choice to watch And Just Like That…, and because, to me, it is a show that exists is perfect halves, making it ideal ambient television.

The sequel series to Sex and the City, though seeming to hit its stride in what I have seen of season 3, has, through two seasons, come off as half-bad; a near fifty-fifty split of unnecessary-slash-out-of-touch and honoring the spirit of the original series in a way that makes me want to keep watching. Of cringe attempts at forced relevance and moments of real depth and warmth in spite of them. Of being utterly predictable in a way the original series never was and possessing the rare ability to, at times, be both funny and poignant.

While I had put the show on as background to keep me from overthinking some editing work I had put off for too long and now absolutely had to do, it was this certain poignancy that pulled my already fragile awareness away from my work and toward a deeper contemplation that paralleled my watching.

At the start of the episode, Carrie meets Lisette for drinks at a crowded, brown-hued bar. There, Lisette, a young jewelry designer to whom Carrie sold her iconic pre-war brownstone at 245 E 73rd St in Season 2 Episode 9 of AJLT, complains about the trappings of being single and attempting to date in the age of smart phones.

She laments a sense of longing for simpler times, which, in this case, is the 1840’s; the setting of a new historical novel Carrie is currently working on and the pair is discussing.

“It must have been so much easier being single back then,” Lisette laments, following a mini-rant on stupid…phones with lame-ass texts, “It’s such a messed up time to be dating…I spend every waking hour scrolling, swiping, texting, and it’s all just hurtful or meaningless.”

The scene moves quickly, morphing into a set up in which Lisette, in her frustration, accidentally chucks her phone across the room, where it is redeemed by an attractive stranger, who approaches the pair and begs the question which one of you should I sue? in a bawdy undertone of implication. He also demands to buy Carrie and Lisette a drink.

What really grabbed my attention wasn’t how scripted and predictable it all was, nor how unlikely — though good for Lisette — but that her words felt ripped directly from my own mind and dropped into the script with the awkward force of a heavy hand.

On my end, however, sitting in a chair, in a room, with no sexy stranger approaching to grab my attention or buy me a drink, and with a deep urge to procrastinate, I instead started to think, as one prone to wandering thoughts does, about the 1840s. Then — while Charlotte and Lisa hunted down an Ivy League whisperer named Lois Fingerhood — I found myself counting further back, in centuries, to the 1740s.

Thanks in part to an aunt who has extensively researched our family history, while fully acknowledging the luxury and privilege of being able to do so1, and having had unlimited institutional access to a host of resources in the past, I know a great amount about the ancestors with whom I share my surname.

I know, for instance, that the first in the Henry line from which I descend arrived in America on September 21st, 1742, aboard the ship Francis and Elizabeth, which embarked from Rotterdam in the summer of that year, journeying perilously across the Atlantic, and arriving in Philadelphia, upon which, an oath of abjuration and allegiance to the British Crown had to be signed before a court.

His name, anglicized to Henry a generation later, was actually Christian Heinrich. Born in Schwaigern, Germany on December 13th, 1718, he came to this country as a Catholic fleeing the persecution of the Protestant elites — King William I of Württemberg and Grand Duke Leopold of Baden — who ruled in 1830s Baden-Württemberg.

Settling in Berks County, Pennsylvania he and his family established a farmstead and mass house on a ridge known as Asperum Collem — Latin for Sharp Mountain. The mass house served as both their residence and a clandestine chapel, a pillar if not the sole pillar of the pioneer Catholic community, hosting and housing traveling priests and missionaries who braved the perils and hostilities of traversing the frontier, performing many ceremonies and sacraments for community members, recorded in historical documents as the house of Christian Heinrich at Asperum Collem.

It is easy for me to look at any one of these feats, even if done in the present day — facing persecution in Germany, the journey across the Atlantic, being a legit pioneer, establishing a farm from nothing, and forging a haven and safe house — in isolation and be astounded, let alone in totality. But the accomplishments are even more amazing when weighed against the violent realities of their time.

Risks of commons raids and attacks by French-allied parties, of property and life loss, of the ravages of the French and Indian war, which unfolded all around the homestead and, even amidst the instability before and long after the conflict ended, infiltrated it. Christian Heinrich lived to be eighty years old, dying in 1798.

While I find his story beyond wild and fascinating, records and history indicate that certain exceptionalities, namely bravery in the face of danger, were not an outlier or anomaly among my forefathers, but the standard and rule2.

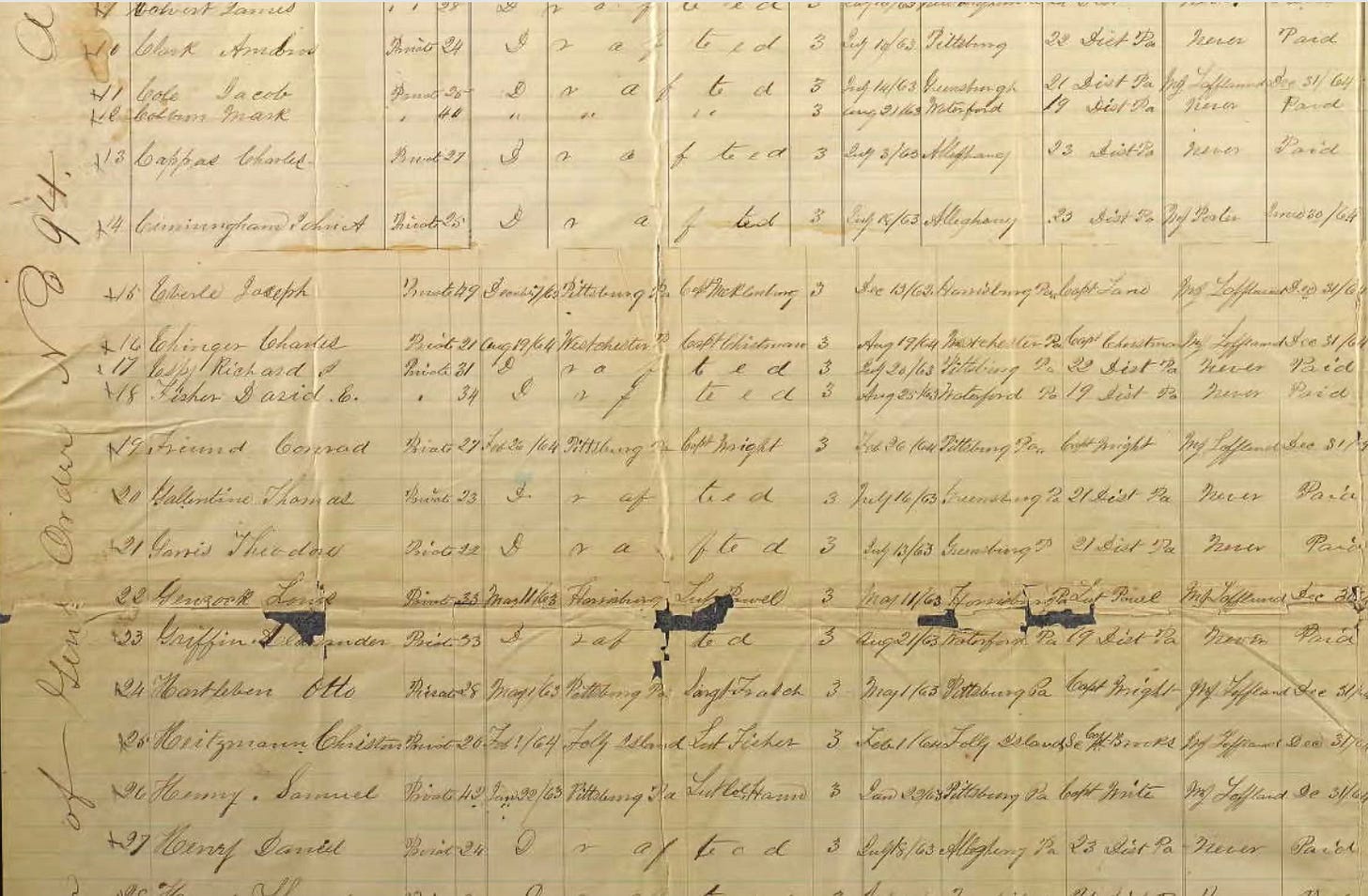

Daniel Conrad Henry, for instance, born a few generations later, in 1843, the time of Lisette’s longing in ‘The Rat Race,’ was my great-great-great grandfather, who enlisted in the Union Army two weeks after the Battle of Gettysburg, mustering on July 18th, 1863. Serving in the 74th volunteer regiment, also known as the German Regiment, due to its majority German-speaking members, he spent the rest of the Civil War fighting in swampy South Carolina lowlands, aiding Union attempts to capture Charleston and maintain the Atlantic Blockade.

And Daniel Conrad Henry also fought in World War I, albeit a different one. Born two generations later, he was my great-grandfather. As part of the 30th US Infantry, 6th brigade, 3rd Division, Company B, he embarked from port in New York City on April 2nd, 1918 aboard the transport steamer Aquitania, and was rapidly integrated into the Western Front upon arrival in France, being schooled in the ways of trench warfare alongside French and British forces.

Rushed to the Marne River to counter the German Aisne offensive, the regiment was instrumental in halting an enemy advance at Château-Thierry, making a stand that earned the division the nickname Rock of the Marne.

My great grandfather’s individual efforts were crucial, earning him a Silver Star and a Distinguished Service Cross, the second highest military honor for bravery, the proclamation stating, “After many other runners had been killed or wounded, Private Henry carried several messages from platoon to company headquarters. At this time the enemy had crossed the Marne River, and the route followed by Private Henry was exposed to heavy artillery and machine-gun fire.”

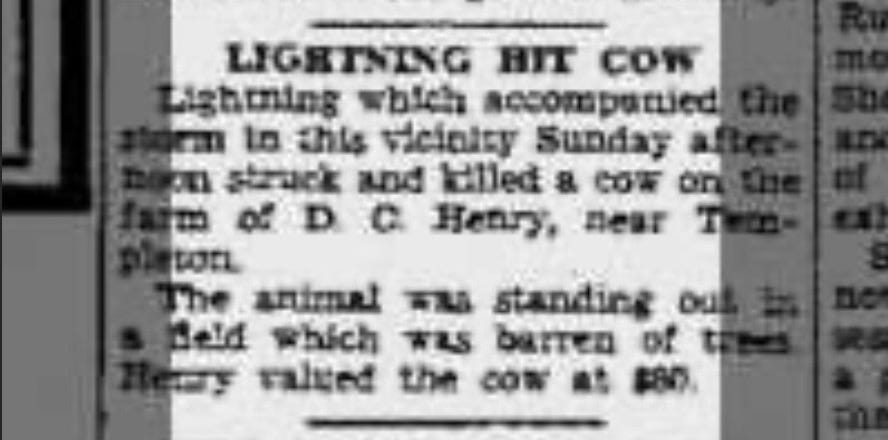

Following the war, he returned home to Kelly Station, Pennsylvania, a small mining town on the banks of the Allegheny river, aboard the Regina De Italia. He became a minister, once again made the news in September of 1937, when lightning struck a cow on his farm, and died twenty years later. Tales of his heroism weighed heavy on my childhood imagination.

Just like Lisette’s desires, the general notion that overcame me here is one I have wrestled with before. The ever-branching odds through time that have landed me here, in this exact place at this exact moment, and wondering what I am supposed to do with it, if anything at all?

Daniel Conrad Henry, the second one, could have easily ended up like so many others while running messages at Château Thierry, vanquished by the heavy artillery and machine gun fire of an enemy who crossed the Marne. But he didn’t. And neither did the generations that preceded or followed his. And so here I am.

Over a century later. Sitting in a comfortable chair. Wondering if the intermittent fasting is actually working, contemplating, for no reason, how I would perform in a fistfight versus opponents of staggered size and skill, worrying to what extent exposure to blue light past 10:00 PM impacts my delicate sleep, and also annoyed that Kim Catrall did not reprise her Sex and the City role as Samantha and I am, at the moment, stuck watching her lesser replacement Seema, similarly named for, I fathom, subconscious acceptance by Samantha ride-or-dies much more begrudging than I but too big of fans to skip the new iteration all together.

I struggle to wonder if my ancestors endured all they did simply so that I could sit here and watch And Just Like That…. I have come to accept Lisette’s desire to live in the 1840s for means of simpler communication as shoddy idealism, as even with a read receipt, I have enough anxiety as it is over things like is this too many exclamation points for one text message, despite the near entirety of it bursting with the need for exclaim.

If you add in the uncertainty and prolonged time frame of, say, the Pony Express or a carrier pigeon, I’m just straight ravaged in my forced waiting and probably don’t fare well, as I learned recently when trying to send my friend Aaron a picture of a store I came across dubbed ‘The Beef Jerky Experience,’ but had zero cell service for days while camping near the small town it was located in.

But I can’t help but think if I wouldn’t welcome it, or at least trade it for these comforts for, say, a day, or, thirty seconds, as a means of discovering a forced bravery or to feel like I’m making some more overt or outward impact on the world.

Though, as I started to weigh this, thinking of a civil war amputation kit I recently saw on exhibit at the Smithsonian Museum of American History, grimacing at the image in memory of what was, basically, just a rough-ass saw, text message punctuation fresh on my mind too; Carrie Bradshaw made me feel more seen than I maybe ever have been.

About a quarter of the way into the episode, Carrie, the drafting of her historical novel interrupted by hundreds of rats overrunning her serene Gramercy garden, dictates a text message to her boyfriend Aidan, who going off of memory, is a sexy carpenter type who she dated in seasons 3 and 4 of the original series, and is now dating again, long distance, as he was forced back to Virginia when his youngest, Wyatt, got into an alcohol-related car accident in season 2, episode 10. This first text message she dictates in the episode concerns both the rat infestation and her desire for Aiden to be there:

Hi, Aidan, period. You won't believe this, comma, but turns out, comma, hiding in our beautiful, comma, bucolic backyard are rats. Exclamation point. Many, many rats. Exclamation point, exclamation point, exclamation point.

I'm upstairs because I don't know if they can do steps. Exclamation point. And I forgot to lock the back door, so they can probably push it open if they work together as a team. Exclamation point, exclamation point. Anyway, a guy's gonna come tomorrow to clear the yard, but I really, comma, really wish you were here. Period.

All at the same time, watching Carrie vocalize mid-sentence commas and probably too many exclamation points makes me feel like I am not alone in this world, and like I’m watching myself, which is fitting, as I have come to accept that my ultimate goal in life is probably being Carrie Bradshaw.

Following the text message, which Carrie ended up deleting, feeling it broached the thick boundaries they put in place following Wyatt’s crash, Aiden, as if having received the deleted message psychically, comes up from Virginia and surprises Carrie, being let in by one of the gardeners removing the backyard rats nest, and scares her in her closet. After spending some quality time together, and talking through the difficulties of their long distance relationship, Aidan heads back to Virginia.

Shortly after he leaves, Carrie dictates another text to Aidan, with slightly less punctuation this time, asking for his thoughts on a table she has been eying up for their new Gramercy pad, which is in dire need of being furnished.

Hi, love, period. Hope your flight was uneventful, period. Listen we need furniture, exclamation point. I've been stalking this table online, I'll attach at the end. It's got woodwork, like you, and style, like me. And it's a little weird, like us right now. And I'm really afraid someone else is gonna get it.

Carrie ends the message by instructing Aidan to, Let me know your thoughts ASAP, and follows it up by sending a picture of the table she loves.

The next day, at lunch with Miranda and Seema, Carrie reveals that Aiden’s response to what she describes as her, “impassioned text about how much I love this table,” was an immediate big, simple thumbs-down emoji. And this set Carrie off.

Miranda asks Carrie if she responded with a middle finger emoji, to which Carrie replies in the negative because she is, “an adult who knows how to communicate.”

Carrie spends much of the rest of the episode obsessing over Aiden’s emoji response or her inability to stop fixating on it. That is, until her fixation culminates in the blue-tiled bathroom of a restaurant that only serves guacamole, where she dictates another paragraph reply, verbalized punctuation even more fleeting, before deleting it again. Only this time, Carrie drafts a second message and actually sends it. A single, simple, rolling eyes emoji.

The saga concludes (for now) when Carrie says to Miranda in the aftermath, “Here, I thought I had this big victory with him. You know, that we could be in touch, but texting and emojis are not a relationship. A relationship is standing across from someone and saying, ‘What do you think?’ And then they say, ‘What do you think?’”

In the end, Carrie’s use of the word victory really stuck with me. If Lisette’s harkening to the nineteenth century sent me on a thought spiral of weighing my forefathers of the time, fighting bravely in wars bookmarked by victory, while I half-atrophy and doom scroll here a quarter way through the twenty-first, then Carrie’s choice language brought up something I had not considered before.

What if the existential distress Aidan’s emoji response caused Carrie, 2025 present day, while nowhere near equal in physical danger or threat of death, mirrors, to some degree, the existential distress of crawling out of a trench halfway across the world in 1918 France.

What if all dread is actually echoing the same anxiety: to be exposed. To cross the Atlantic or embark for the Western Front. To hit send on a message not knowing if it will ever be returned. To put yourself out there, uncertain of eventual reciprocation. In any case, it seems to me that the present moment is really nothing more than a body and brain bracing against what it can’t predict but so badly wants to, wondering, in each instance, if this is the time you don’t come back from it. Be it death in a real, physical sense, or in a emotional, spiritual one.

I laugh at suggesting the possibility that the great battlefield of our time might be a digital one, fighting the indifference of a cusp boomer parent or slacker co-worker or checked-out lover whose whole arsenal of dialogue has never evolved from, or, eroded by time, devolved to, not machine guns or heavy artillery, but a stable of three emojis: a single yellow smiley and the two thumbs binary, in hopes of achieving even minor connection.

Still, I like to believe that there is meaning somewhere in all of this. That, buried in the history of all these exchanges, is a through line across time that enduring discomfort matters. Even if that discomfort is putting words out into the world and hoping they are perceived as meaning what we meant. Carrie thought she had won a victory with Aidan. And maybe she had. Because maybe the victories and battles we’re left with are not the same as the ones my ancestors knew. No raids, or mustard gas, or, praise be, trench foot, and no medals or decorations of valor, just an LED screen and a blinking cursor and a vague ache to be known beyond the depths of a single thumbs down.

And just like that comma

I couldn’t help but ask em dash

not only if that’s okay comma

but what if this is our trench now question mark

Footnote: I recognize that my ability to trace this family history is a privilege—one tied to the fact that my ancestors came to this country voluntarily and, though fleeing religious persecution, their story unfolds in the wider context of settler-colonial systems that erased and displaced Indigenous communities.

Footnote: As I reflect on the military service of my ancestors, I want to be clear that my intention is not to glorify war or romanticize its violence, nor the often troubling history of American military expansion and imperialism, but to consider how the fear, courage, and uncertainty they experienced, when faced with the very real threat of imminent death, compare with my present day life and anxieties.